The Threshold of London

In the ancient borough of Southwark, travel, piety, and merry-making have enjoyed a curious co-existence.

FOR NEARLY TWO millennia, Southwark has stood just across the Thames from the City of London – facing it, feeding it, sometimes (I’d like to think) rivalling it, perhaps more often scandalising it. At the very threshold of the capital, for centuries our position on the South Bank has made Southwark the place where travel into and out of London was channelled, where devotions were performed and gods implored, and where the amusements that proved too much for the City’s restraints flourished. These three themes – travel, piety, and merry-making – recur throughout the long history of this, the oldest borough in the world.

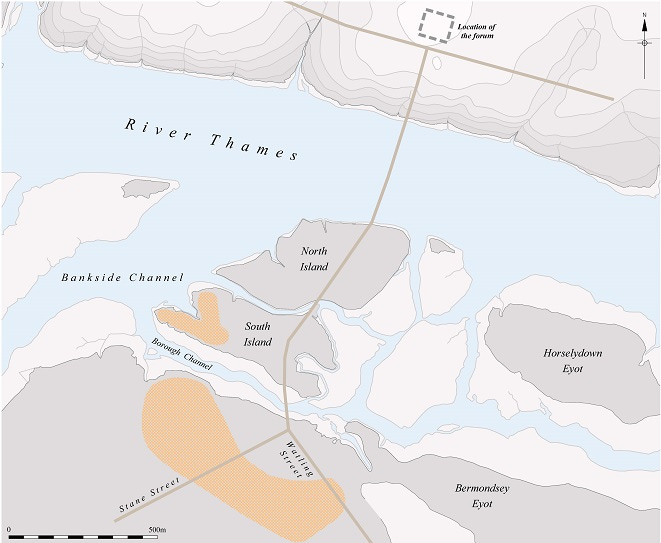

As so often on this island, it all begins with the Romans. Londinium was founded around AD 47–50, a walled city with a basilica, a forum, wharves, and many merchants. This entire enterprise was only possible because of geography: here was the lowest practical point on the Thames for a permanent bridge. London Bridge was the hinge of the realm, connecting overland routes of travel to river trade and the seas beyond. If there was a bridge with a city on one side, there was bound to be some settlement at the other end of it; somewhere the waifs and strays, the has-beens and the kicked-outs, could wend and wander their way. Thus was Southwark born. We know that by AD 72 it already had buildings — the Borough High Street, still our central artery, runs in unbroken continuity from then to this very day.

From its end branched two great Roman roads: Stane Street led to Chichester (or Noviomagus Reginorum) while Watling Street ran from Wroxeter (Viroconium Cornoviorum) in Shropshire through St Albans (Verulamium) and London, across the Bridge, and onwards to Canterbury. Southwark was the hub of this network. Boats unloaded their wares in the Pool of London, merchants and pilgrims came by road, and all of them passed through here. Like the great roads leading out of Rome itself, the Borough High Street’s ancient antecedent was lined with tombs and shrines to pagan deities, with temples where travellers made offerings for a safe journey or gave thanks for arrival.

Constant and furious building in these parts has been a gift to archaeologists and helps shed better light on Roman Southwark. In Lant Street, the remains of a young woman were found, buried with a folding knife whose ivory handle was carved in the form of a panther. The only other example ever discovered was found at Carthage. At Tabard Square, behind the current Anglican parish of St George’s, a temple precinct has been unearthed. In 2002, archaeologists found there a tablet inscribed “to the Gods of the Emperors and to the God Mars Camulus, Tiberinius Celerianus, a citizen of the Bellovaci, moritix, of Londoners the first…” before trailing off.

His title or office of moritix has puzzled Latin linguists, though it seems to denote a seafarer or merchant whose wares travelled by boat – fitting for Southwark. Bellovaci refers to the Celtic tribe who lived around Beauvais in northern France, giving some idea of where travellers and traders in Londinium hailed from. Camulus was a Celtic god – after whom Colcehster was first named – so referring to Mars Camulus shows the hybrid nature of the deities worshipped by people passing in or through Romano-Britain. Academics have postulated the inscription dates from as early as 161 or as late as 180 – the year Marcus Aurelius died.

Whoever Tiberinius Celerianus was, we can be grateful to him: not just for being the first moritix of the Londoners but because this is the earliest monumental inscription so far discovered that refers to Londoners. Already in the second century Southwark was home to traders from Gaul, invoking hybrid gods, linking Britain with the wider world.

With the passing of centuries, empires rose and fell, but Southwark’s role altered little. When Christianity came, this was still the approach to the city. The land here was much marshier than the north bank, though pockets of firm ground flanked the High Street. Westward was Lambeth Marsh – now Lower and Upper Marsh on our street maps – which remained largely undeveloped until the late eighteenth century.

For mediaeval Southwark, however, the High Street was the solid ground around which the Borough grew. Here in 1106, the Augustinians or Austin Canons established the great church of St Mary Overie (or St Mary Overs), thanks to the benefaction of two Norman knights: William Pont de l’Arche and William Dauncey. The nave was soon rebuilt thanks to the generosity of William Giffard, the Bishop of Winchester whose vast diocese sprawled from just west of that city all the way until London’s Bermondsey where Rochester’s diocese began. (North of the river was the domain of the Bishop of London.)

As England’s riches grew and London became the centre-point of the realm, Southwark was the coming-to and going-from place. The priory, just outside of the City and on an important travelling route, attracted the generosity of kings, bishops, lords, and merchants. Though never a large house – only fifteen to twenty canons, sometimes a few more – Southwark Priory played an outsized role. Martha Carlin in her excellent book on mediaeval Southwark points out the Bishop of Winchester reserved to himself the right to install the prior, and the priory church was often used for ordinations, consecrations, diocesan courts, and other solemnities. The Bishop maintained his London residence, Winchester Palace, nearby, the last remnant of which is a wall or two of the Great Hall, still visible beside the Clink Gaol.

There was a very active devotional life associated with the Priory and its lay confraternity brought in Southwarkers and Londoners of all classes. In the fifteenth century we can find admitted to this confraternity the parish priest of St Mary Magdalen at Bermondsey, the wife of a Southwark wax-chandler, and Thomas Asschewall, the Carmelite friar who became Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge – to mention just three of many others. The Priory and its confraternity provided burial services, requiem Masses, and education to the people of Southwark. This was no isolated monastery but a community at the very centre of travel and trade.

Piety here also took the form of pilgrimage. After St Thomas Becket’s martyrdom in 1170, Canterbury developed into one of the great shrines of Europe. Pilgrims from across England funnelled through Southwark, setting out down Watling Street. Geoffrey Chaucer immortalised them in The Canterbury Tales, beginning at the Tabard Inn in the Borough High Street:

Bifel that in that season on a day,

In Southwerk at the Tabard as I lay

Redy to wenden on my pilgrymage

To Caunterbury with ful devout corage,

At nyght was come into that hostelrye

Wel nyne and twenty in a compaignye

Of sondry folk, by aventure yfalle

In felaweshipe, and pilgrimes were they alle,

That toward Caunterbury wolden ryde;

The chambres and the stables weren wyde,

Astonishingly, the Tabard Inn’s chambers and stables survived until 1873, long after it had ceased to function as an inn.

Yet Southwark was never merely a place of piety. It was also London’s playground, beyond the reach of the City fathers and their restrictions. The High Street was crowded with coaching inns, taverns, and hostelries – many founded during the Middle Ages but reaching their apex in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Travellers from the Continent would disembark at Dover, head overland, and find themselves here first before reaching the City: able to rest, to eat, to drink – and to divert themselves.

Theatres like the Rose and the Globe staged Shakespeare’s plays to eager audiences while bear-baiting pits and cockpits offered bloodier entertainment. Ladies of the night plied their trade and the Bishop of Winchester did not disdain to license and tax them, earning them the nickname of the “Winchester Geese”. Many ended their days in the Cross Bones graveyard, a stone’s throw from where the Church of the Precious Blood now stands.

This juxtaposition of sanctity and license was Southwark’s peculiarity. Priors said Masses and pilgrims prayed for miracles while, a few steps away, players declaimed on stage, bears fought dogs, and men sought women of the night. The strictures of the City did not apply here; this was a borderland where the ordinary rules loosened.

Some of the old inns survive. The best preserved is the George Inn, now owned by the National Trust and run by the Greene King brewery. The George still has the old galleries off which travellers would have rented rooms for the night – often several to a bed. Only half of its galleried yard remains.

The inn’s name harks back to the mediaeval parish of St George, of whose legacy our now 175-year-old Catholic cathedral of St George is an inheritor. In the same vicinity where Romans raised mausolea and temples, Christians built a church to the patron saint of England, and today we continue to gather under his protection, whether to pray or to drink – ideally both.

These themes of Southwark hold together. Movement: Roman roads, medieval pilgrims, Elizabethan actors, and modern commuters. Piety: temples, priory, cathedral. Merrymaking: taverns, theatres, games, and pleasures of every kind. Southwark has always been a threshold — between north and south, between city and country, between sacred and profane. In this mixture, this concurrence of holiness and mischief, the oldest borough in the world speaks to us still.

Hello friend, I’m trying to find new interesting writers, so I thought I’d introduce myself with an article.

Hope that’s okay, pleasure to meet you.

https://open.substack.com/pub/jordannuttall/p/the-plague-in-asia?r=4f55i2&utm_medium=ios

Very interesting article - thanks for sharing it with your readers. LF