How to Make a Pope

The Argentine upbringing of Jorge Mario Bergoglio

“How do you make a pope” is a question people have been asking themselves for centuries. Given the obvious contingencies of time and place, it is impossible to figure out a failproof method of getting one elected.

There used to be a way of making sure one wasn’t: various European monarchs claimed the jus exclusivae right of veto across the centuries. The last attempt to use it was 1903 when the Prince-Archbishop of Krakow, Cardinal Puzyna, invoked it on behalf of the Hapsburg emperor to veto the election of Cardinal Rampolla.

The conclave refused to accept the emperor’s claimed veto and continued voting, but Rampolla decided to withdraw his name and the splendid Patriarch of Venice, Cardinal Sarto, was elected Pope St Pius X instead. Within the first year of his papacy, Pius X issued an apostolic constitution specifically condemning and forbidding the purported jus exclusivae veto.

But pontiffs, supreme or otherwise, are mere mortals, and — clerical offspring aside — men are not made by cardinals but by their families and the circumstances of their upbringing.

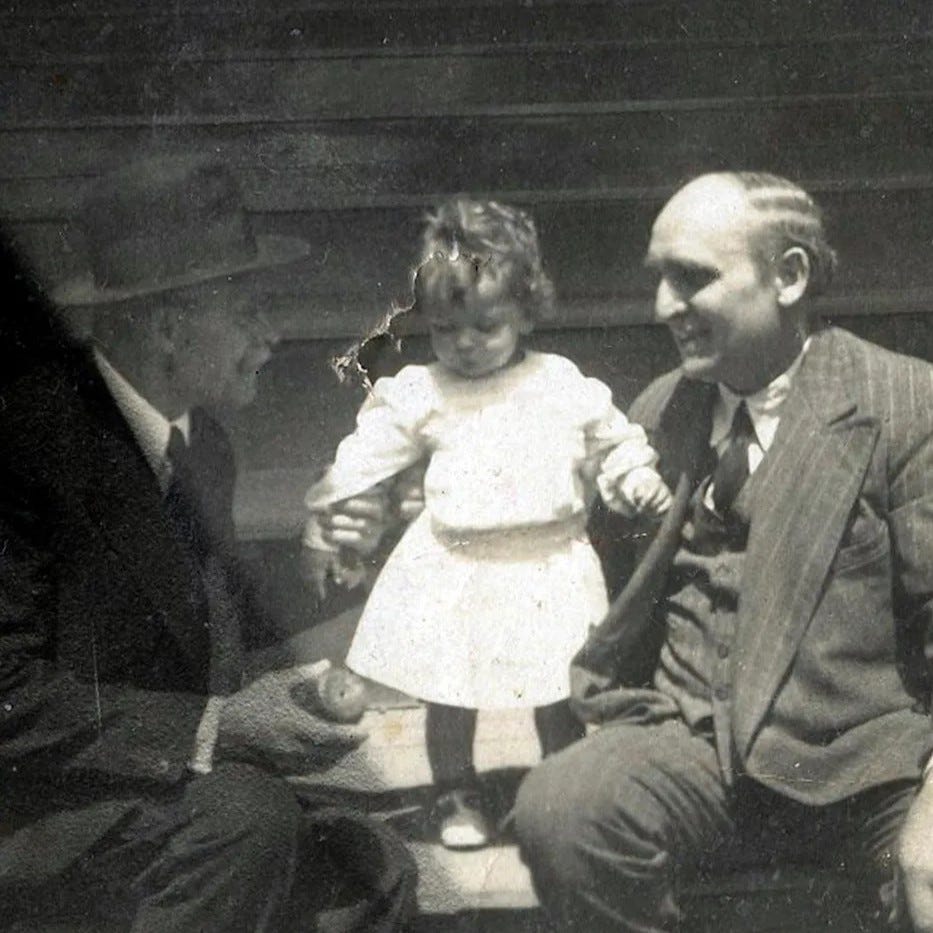

The late Pope Francis was born Jorge Mario Bergoglio on 17 December 1936 in Buenos Aires, Argentina to an Italian immigrant couple: Mario Giuseppe Bergoglio, a railway worker turned accountant, and his wife Regina Maria Sivori.

During the first weeks of the future pope’s life, the mother’s nurturing of her first-born was aided by the Little Sisters of the Assumption who had established a community in the Bergoglios’ Flores neighbourhood in 1932. Mario was a member of the Fraternity of Our Lady of the Assumption while his wife joined the Daughters of St Monica, both lay communities attached to the French-founded order of sisters.

Mario had arrived in Argentina in 1927 when Jorge Mario’s grandfather, Giovanni Angelo Bergoglio, emigrated from Piedmont with his wife and six children to join his brothers who owned a paving company in the Buenos Aires province – the mostly suburban and rural district flanking the capital and reaching deep into the countryside.

The advent of the Great Depression in 1929 forced the family to move to the more modest district of Flores in the city of Buenos Aires proper. Mario trained in economics but supported himself with menial jobs before he landed a position as an accountant for a railway company. He married Maria — Argentine-born but also from a Piedmontese immigrant family — in 1935.

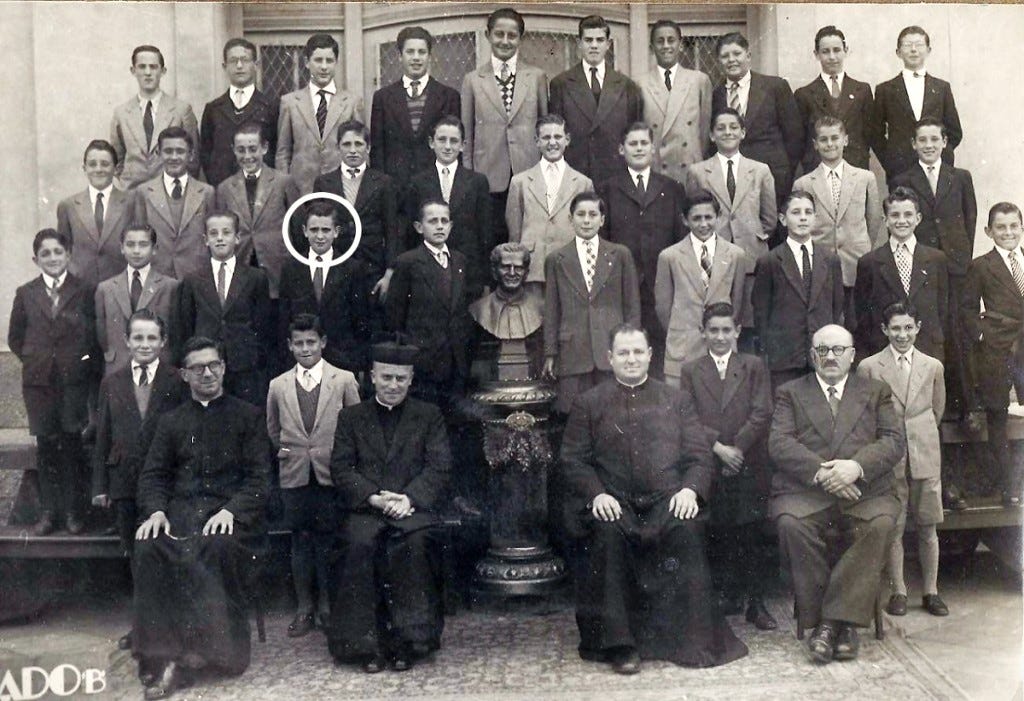

Decades later, Father Bergoglio recalled his family being “spiritually nourished” during his childhood by the Salesian Fathers at the stunning Basilica of María Auxiliadora (Our Lady Help of Christians), where young Jorge Mario took part in processions and had his confession heard. This relationship with the Salesians only grew when Jorge Mario (thirteen years old) and his younger brother Oscar were sent as boarders to the Salesian-run Colegio Wilfrid Barón de los Santos Ángeles just outside of Buenos Aires.

“I was immersed in a way of life designed so that there wasn’t time to be lazy,” Bergoglio wrote in 1990. The young boy was “submerged” in a world in which “the most natural thing was to go to Mass in the morning, as well as having breakfast, studying, going to lessons, playing during recreation, and hearing the ‘good night’ of the Father Director”.

The Catholic culture of the school encompassed sport, theatre, study, and pious devotions, as well as practical learning through crafts and hobbies. The Salesians “made us feel that we could trust, that they loved us, they were able to listen, they gave us good opportune advice, and they defended us both from rebellion as well as melancholy”.

With his love of chemistry, Jorge Mario went on to secondary school at the Escuela Técnica Hipólito Yrigoyen that specialised in the subject, part of the system of technical schools begun under the presidency of Julio Roca in the 1900s.

Institutions like these received increased attention and investment during General Juan Perón’s first period of rule from 1946 as his government sought to increase the number skilled workers available to expand Argentina’s domestic industry and reduce its dependence on foreign capital.

Bergoglio was ten years old when the charismatic army officer came to power on the back of broad support from the unions whose favour Perón had curried vigorously during his period as labour minister in the Ramirez and Farrell juntas. Perón formed a somewhat hodgepodge ideology he christened ‘justicialism’ based on the three pillars of social justice, economic independence, and political sovereignty.

Argentina, a country used to being ruled by competing factions of upper- and upper-middle class elites, suddenly found itself under the control of a government that positioned itself very openly in favour of the working and lower-middle classes. At the same time, it was totally devoid of the divisive Marxist thinking of class-based conflict. Solidarity amongst all Argentines, Perón and his supporters argued, required a rebalancing of factors that advanced the material condition of the working classes. It was only a bad, oligarchic elite that needed restraining or replacing, not the entire structure of the universe.

Developing the industries that employ these workers (and paying them well) would allow Argentina’s ownership classes to control the national economy instead of foreign (usually British) companies that had gained an advantage in the preceding decades. Economic independence across all classes would then strengthen the political independence of the Argentine state, allowing it greater freedom of movement to make its own social and economic decisions — in particular without recourse to the United States.

Ideology aside, the everyday realities of Perón’s first period in power relied upon a cult of personality surrounding the general and his popular wife Eva. Individuals, families, and institutions that were neutral, ambivalent, or antagonistic to the President were subjected to intimidation and the full animus of the state.

A number of Catholic intellectuals commended the early programme of Peronism as well as the social and economic rights embedded in the 1949 constitutional reform. (Religious instruction, for example, was also allowed to return to state schools in a country whose taxpayers were overwhelmingly Catholic.) But rifts soon developed over a number of political issues relating to Perón’s desire to increase his control of Argentina and resentment at church leaders’ zeal for maintaining their independence.

By 1954 the General openly turned against the Church and moved to introduce divorce and legalise prostitution, as well as proposing a constitutional separation between the Catholic Church and Argentine Republic which had never before existed. Perón’s high-spending boom-reliant economic policies continued even though the bust had come, yet the general and his leadership looked for scapegoats elsewhere.

Dissatisfaction amongst many factions of the intellectual, commercial, political, and military elites — whether Catholic or secular in their mentality — festered to the point where Perón was overthrown in a 1955 military coup lead by the Catholic-inspired General Eduardo Lonardi. (Perón’s exile and eventual return to the presidency in 1973 is another story entirely.) Lonardi himself was shuffled out of his job by his fellow generals two months later.

The years 1946 to 1955 were not just ones that profoundly influenced Argentina but, from the age of ten to nineteen, formed the young Jorge Mario Bergoglio.

It was an aspirational society with a fluid barrier between the working and middle classes in which hard work could prove immensely rewarding. Yet it was also one of political and economic instability which meant hard-won gains could disappear overnight and anyone too proud today could be eating humble pie tomorrow. (But you could always blame the oligarchs.)

The mindset Peronism fostered in Argentina — even amongst its vociferous opponents — valued helping the workers achieve the dignity of a decent middle-class existence. Because of Perón, divisions between “left” and “right” were obscured to the point of rendering these terms worse than unhelpful. The social, political, and economic axes of Argentina today are still defined according to the mentality and divisions that Perón fostered.

In the year Perón was overthrown, the young Bergoglio received his secondary school certificate in chemistry and worked a number of jobs — including as a bouncer at a nightclub and a minor employee in a chemical lab who combined analysing test results with sweeping the floors.

The 21st of September is the first day of spring in Argentina and traditionally “Students Day” when secondary school and university students celebrate the change of season. According to interviews he gave while he was Archbishop of Buenos Aires, the 21-year-old Jorge Bergoglio was on his way to a Students Day party when he stopped in to a church to go to confession. It was then and there, the late pope said in interviews, that he discovered his priestly vocation, and he joined the Society of Jesus the following year.

Jesuits traditionally undergo a long formation so it was a decade before he was ordained a priest in 1969. Fr Bergoglio was consecrated a bishop in 1992 to serve as an auxiliary in Buenos Aires. When Archbishop Quarracino’s health was fading in 1997, Bishop Bergoglio was appointed coadjutor in the see and succeeded as Archbishop of Buenos Aires when his predecessor died in 1998.

St John Paul II appointed him to the College of Cardinals in 2001, and Cardinal Bergoglio was elected supreme pontiff in the papal conclave of 2013 following the abdication of Benedict XVI. Taking the name of Francis, Papa Bergoglio served as the chief shepherd of the Catholic Church until his death on Monday morning.

Pope Francis, requiescat in pace.